Category: Ireland

Christmas in Ireland

In Gaelic (Irish language), Christmas is “’Nollaig’” and Happy/Merry Christmas is ‘Nollaig Shona Dhuit’.

Christmas is celebrated in a big way in Ireland, with a large part of the country shutting down between Christmas Eve and New Year’s Day. It used to be even longer in days past: it was celebrated by Catholics until the Feast of Epiphany, sometimes called “Little Christmas” or “Women’s Christmas”, on 6th January!

Long before there were Black Fridays, Ireland had its own version for a while: in the second half of the last century, on the 8th of December, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, people from all over the country would descend on Dublin for their Christmas shopping. With the spread of shopping centres around the county and the rise of e-commerce, this relatively modern tradition has however mostly died out.

In those days, the 8th also used to be the day that people started decorating their houses. Nowadays, some people start in November, while longer ago houses weren’t decorated until Christmas Eve.

Returning to modern days, in the run-up to Christmas children often go to “Pantos”, a shortening of Pantomine. They are a kind of musical comedy, performed on many stages and in theatres.

Christmas Eve is the day that traditionally people in Ireland use to travel to their families. There are still quite a few people who will put a candle in the window. This was originally done to welcome Mary and Joseph. Former President Robinson placed a candle in the window of the Áras an Uachtaráin – the official residence of the President of Ireland – to remember the Irish diaspora. But we are sure arriving family members appreciate it as well after an often long journey to celebrate Christmas with the family.

Christmas Masses used to be at midnight on Christmas Eve. Thankfully mass times nowadays are a bit more accommodating.

Some people, and we really mean some, partake in a swim in the sea on Christmas morning. As you can imagine, this is a pretty cold affair. It is mostly done for charity, but also for fun and to keep up the tradition.

On the 25th, people sit down with their families for the Christmas meal, usually starting late afternoon. For many it is not a Christmas dinner without turkey and cooked ham, preferably with carrots, brussels sprouts, and of course mashed potatoes and roasties. And for dessert a Christmas Pudding and/or rich Christmas Cake. In some areas, Cork for example, a portion of spiced beef is also a must. Often the turkey and ham leftovers are still being eaten cold on sandwiches for several days afterwards!

The day after Christmas is called “St. Stephen’s Day” and is an important day in the horse racing calendar. Those not attending, mostly use the day for relaxing.

Less widely celebrated now, but very popular in the past was the “Wren Boys Procession/Wren’s Day/Hunt of the Wren”. A wren is a small bird. If still celebrated now, a fake is used, but in the past, it was a real bird that was hunted, killed, and put on top of a pole or bush and paraded around, with the participants dressed up in all manner of costumes. Whilst going from house to house a song was sung:

The wren, the wren, the king of all birds

St Stephen’s Day was caught in the furze

Her clothes were all torn – her shoes were all worn

Up with the kettle and down with the pan

Give us a penny to bury the “wren”

If you haven’t a penny, a halfpenny will do

If you haven’t a halfpenny, God bless you!

This would later develop in carollers going from door to door, but that has now mostly stopped as well. But you will still hear carollers in shopping streets and centers, still collecting money. But as it is now for charity, hopefully, they get more than pennies.

The end of the Christmas celebrations was traditionally, as mentioned, on 6th January. It was called “Women’s Christmas” because that day the men are supposed to do the work in and around the house, giving the women a chance to meet and chat. In recent years, this tradition has had a bit of a revival with women meeting up for lunches, etc. on this day.

From “Say Prunes” to “Say Cheese”

The creation of permanent images began with Thomas Wedgewood in 1790, but the earliest known camera image belongs to French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. In the late 1830s in France, Joseph used a portable camera to expose a pewter plate coated with bitumen to light, so recording images for the first time. Together with Louis Daguerre he experimented using different materials (copper, silver, chemicals) and their camera became (relatively speaking) popular. But it was an expensive hobby and the “film” needed to be exposed to light for 15 minutes!

Further developments followed with “wet plates” in the 1850s and “dry plates” in the 1870s. In the 1880s a George Eastman started his company in the US, called Kodak and he made the first camera that was accessible to a much larger audience, in other words, the middle classes.

John J. Clarke, NLI Collection

And that included John J. Clarke, who came to Dublin from his Castleblayney, Co. Monaghan home to study medicine at the Royal University. During his time there, 1897 to 1904, he took many pictures. Most of them in and around the Grafton Street and St Stephen’s Green area, but also Portobello, Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire today), and Bray. What is remarkable is that he took pictures of everyday people as they were going about their business, not posing. This allowed him to capture real-life scenes from the daily lives of Dublin’s men, women, and children. And that, in turn, gives us a wonderful insight into the Dublin some of our ancestors would have lived in.

A large number of photographs survived and were donated by his family to the NLI. You can see most of them on the NLI website, by clicking the logo below.

In the late 19th century, different aesthetic and behavioural norms required keeping the mouth small, which led to photographers using “say prunes”. By the mid-1940’s, smiles became the norm which led to the introduction of “say cheese”.

Why not dig out your family photos and try to see if you can date them and name who is in the photo? If you are having difficulty dating them, why not share online and ask other family historians to use their expertise along with your knowledge of your family. We have witnessed so many puzzles by crowdsourcing the answer online.

Enjoy!

Women in Irish History

The Irish Government has launched a new online resource for the Decade of Centenaries – it is called Mná 100 (Women 100). The updated website Mna100.ie includes original research with some previously unseen photos and historic documents drawn together in new and innovative ways.

This new resource will reflect on key themes, such as the role of women in advocating for Ireland internationally; the role of women’s organisations during the Campaign for Independence and the Civil War; women in the Oireachtas (Irish Parliament); and the stories of the pioneering women who were trailblazers within their chosen professions.

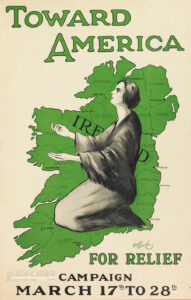

We recommend the special curated short film for Mná 100 called Toward America. The film looks at the American Committee on Conditions in Ireland and the foundation of the Irish White Cross. The piece is grounded in original research, with a wealth of images from private and public collections in Ireland and the United States. It is exclusively curated for Mná100.

The 100 Year Journey will guide the viewer through the journey of women through the 20th century and early 21st century. The 100 Year Journey showcases women who implemented change, through an easy-to-navigate timeline that includes images and illustrated biographies, with personal archive material and animated content.

Mná 100 was launched both simultaneously in Ireland and in New York with guest speakers from Glucksman House, NYU, and the Irish Consul General in New York.

In family history, we often find it more difficult to trace female lines. We welcome and encourage all new resources that are working to uncover women in Irish history.

James Hoban, the Irishman who built the White House

James Hoban was born around 1758 in Desart near Callan, Co. Kilkenny, Ireland. His parents were Martha Bayne and Edward Hoban. We know he had three siblings – Joseph, Philip, and Ann – but there might have been more. The estate they lived on was owned by Baron John Cuffe. It is not sure what the position of the Hoban’s on the estate was, but they were not very well off.

James learned the skills of a carpenter on the estate. He was given the opportunity to go to the Dublin Society’s School of Architectural Drawing in 1780. This society was and is an Irish philanthropic organisation founded on 25 June 1731 to see Ireland thrive culturally and economically. It would become the Royal Dublin Society in 1820. They would not charge fees to talented but poor students. This is how James became an architect.

He specialised in the Georgian style then popular in Ireland. An excellent example of this style is Leinster House. It was constructed as a home for the Duke of Leinster and designed by the famous architect Richard Cassels. In 1815 it was purchased by the Dublin Society, the same society that had sponsored James’s education. In 1922 the newly formed Irish state rented the main meeting room as a temporary chamber for its parliament. It would become its permanent home.

Back to James: his first job was that of an apprentice to the school’s principal Thomas Ivory. But it was in the United States that he would make his fame. He moved shortly after the Thirteen Colonies had gained their independence, presumably attracted by the possibilities for advancement in the United States. He went where his work took him: first, in 1785, he worked in Philadelphia, then in 1787, he went to Charleston and Columbia in South Carolina, where he designed the Capitol building (burnt in 1865).

The new republic had made plans for a new capital, including a grand home for its president. In 1791 a French-born architect called Pierre Charles L’Enfant was hired, who chose the location. However, his designs did not meet the approval of the president’s commissioners as it was deemed too opulent. L’Enfant was fired and an open competition was held to find a replacement. James Hoban entered the competition and won. And this is how he got to design and manage the construction of possibly the most famous building on the planet right now: The White House.

It is sometimes said he modeled it on Leinster House. We rather believe they are both simply examples of the same Georgian design style, which is called Neoclassical in North America. Construction of the White House started in 1793 and was not finished until 1801. And then Hoban had to do it all over again: The first White House was burned down during the invasion by British troops from Canada in 1812, in an attempt by Britain to regain the colonies. This time the job took 3 years, as the building was not completely destroyed.

James also worked as a superintendent on the construction of the Capitol (designed by William Thornton) and designed the State and War Offices in Washington DC (1818) as well as many, many other buildings.

James Hoban was a local councilor in the District of Columbia. He founded a society (Sons of Erin) to help Irish workers with food, medicine, and a roof over their heads when they needed it. He would speak up for immigrants. But he also owned slaves, some of whom worked on the construction of the White House.

James was married to Susanna Sewall. They had 10 children and he had considerable wealth at the time of his death on 8 December 1831 in Washington. He is buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

“Laurels and Ivy, So Green, So Green”

Christmas Customs in Ireland

One hundred years ago, in December 1920 in the Freeman’s Journal, Mary Mackay felt it was essential to share her views about a true Irish Christmas. She looked to the west and south of Ireland where they are “jealous and tenacious of their own national customs and celebrations”. “There we have words and phrases lingering through centuries to tell us”.

26 December is nowadays called “St Stephen’s Day” in Ireland. In the past – and in some places to this day – it was called “Wren’s Day” or in its Irish form “Lá an Dreoilín”. The tradition consists of “hunting” a fake wren and putting it on top of a decorated pole. “The Wren Boys appear, masked, beribboned, and covered with green and coloured wreaths and garlands, chanting the story of the captured wren, which their leader is supposed to carry attached to the top of an ivied pole”.

In her article, Mary Mackay explains that Christmas Day is scarcely noticed in favour of “Little Christmas” or “Twelfth Day” which was the day the festival was observed before the change of calendar. Little Christmas is marked on 6 January and is more widely known as the Feast of the Epiphany, celebrated after the conclusion of the twelve days of Christmastide. In traditional custom, this was the day of a festival in Ireland. In some parts of Ireland, it was and still called “Nollaig na mBan”, literally “Women’s Christmas” and it is the day the menfolk take down the decorations while women relax or meet their friends socially returning home to a meal cooked for them. It is also the traditional end of the Christmas season and usually the last day of holidays for school children.

The article tells us of the old and purely Irish tradition of candles. On Christmas Eve, “custom says that it must be a man, preferably dark-haired, who will light the first [candle]; and all the other will be lit from that flame. They are supposed to be kept burning all night, though that is seldom found practicable; but it is extremely unlucky if one goes out or is quenched accidentally before its time. Then for Christmas wishes …”.

The article tells us of the old and purely Irish tradition of candles. On Christmas Eve, “custom says that it must be a man, preferably dark-haired, who will light the first [candle]; and all the other will be lit from that flame. They are supposed to be kept burning all night, though that is seldom found practicable; but it is extremely unlucky if one goes out or is quenched accidentally before its time. Then for Christmas wishes …”.

In more recent times, and I think appropriate now, is to light a candle in your window for the Irish diaspora in the world. This year, we will light our candle and think of all the family histories we have uncovered and the stories we have shared. From all of us in Genealogy.ie we will light our candle to send a warm glow and message of love to all the Irish and friends of Ireland around the world.

We wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

If you want to read the original article, click on it below to download it.

14 Henrietta Street

Luke Gardiner was a property developer in Dublin in the 18th Century. He developed large parts of Dublin City north of the river Liffey and became very wealthy in the process.

Probably his most upmarket development was Henrietta Street, laid out during the 1720s. This is a very short street, now known for The Honorable Society of King’s Inns building at the top. This is however of a later date, its foundation stone was laid “only” in 1800.

Henrietta Street was aimed at the very top of Irish society: nobility, senior clergy, top judges, and Luke Gardiner himself. Many of them would have seats in the Irish Parliament, either elected or through hereditary rights. For several of them this was their city house, as they also owned substantial mansions down the country.

The houses on Henrietta are very large Georgian buildings. Number 14, of which more below, measures 9,000 square feet over 4 floors and a basement. The basement would contain the kitchens and storage space, it is where the staff would toil. The ground floor would be the main living space for the family. The Piano Mobile or first floor would have several reception spaces for entertaining guests. The top two floors were bedrooms and nurseries.

The houses on Henrietta are very large Georgian buildings. Number 14, of which more below, measures 9,000 square feet over 4 floors and a basement. The basement would contain the kitchens and storage space, it is where the staff would toil. The ground floor would be the main living space for the family. The Piano Mobile or first floor would have several reception spaces for entertaining guests. The top two floors were bedrooms and nurseries.

The first family to live in the house was the family of Robert Molesworth, who was a powerful politician who was created a Viscount in 1715. He was followed by several other rich and powerful occupants, such as The Right Honorable John Bowes, Lord Chancellor of Ireland, Sir Lucius O’Brien, John Hotham Bishop of Clogher, and Charles 12th Viscount Dillon.

That all changed in 1801. In that year, England’s leaders decided to centralise power. They had become worried because of the French Revolution, which has led to unrest in Ireland as well. By convincing and bribing members of Parliament, they succeeded in getting the parliament to vote for its own abolition. Powers were transferred to the parliament in London.

Soon the rich and powerful left Henrietta Street. They were at first replaced by legal people, lawyers, solicitors, barristers, etc. This included Number 14. In 1850, it became a temporary courthouse at the end of the Great Famine, dealing with the affairs of the many bankrupt country estates: the Encumbered Estates’ Court.

When this was no longer needed it was for a while used by the English army as a barracks until 1876. Thomas Vance bought the property and turned it into a tenement, by stripping out all valuable decoration – such as marble fireplaces – and subdividing many of the rooms. Since the famine, many Irish had descended on Dublin and there was a desperate shortage of housing. Just after the turn of the nineteenth century, there were over 100 people living in 14 Henrietta Street. It was an “open door” building, which means the front door was never locked. During the night vagrants would come in and sleep in the corridors.

It had no running water; and only two toilets. It was heated by open fires, which were also used for cooking. Lighting was by means of candles and oil lamps. It was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that gas and electricity was introduced.

Bugs and vermin would also be a continuous problem. It was said that residents arriving in the dark, would kick the stairs to scare away the rats. Floorboards were in a bad state; in many places you could see through them to the floor above or below. In many rooms there were holes in the floor.

Bugs and vermin would also be a continuous problem. It was said that residents arriving in the dark, would kick the stairs to scare away the rats. Floorboards were in a bad state; in many places you could see through them to the floor above or below. In many rooms there were holes in the floor.

Still, 14 Henriette Street was an “A” class tenement. “B” class were worse and “C” class were often sheds or stables.

The famous strike known as the “Lock Out” early in the century was a failure. But it did bring the appalling living conditions of many Dubliners out in the open. Action was delayed because of World War I, the War of Independence, the Civil War, and the creation of the Irish State. Plans were finally made in the 1920s and construction of suburbs started in the thirties. These provided much improved and healthier living conditions, although not the same sense of community. When several tenements collapsed in the sixties, it gave a renewed impetus to the building of modern housing. Apart from more suburban developments, this was also the time that Ballymun was developed. As per above, it was not until the seventies though that the last tenements were closed.

Number 14 was allowed to decay. As part of the Henrietta Street Conservation Plan, the local council bought the house after 2000. It started a long renovation process and it opened to the public in 2018, telling the story we have related above. For more information click here.

Tenement living around 1900:

An impression of a tenement room around 1900.

No blankets. Instead, coats were used to keep warm during the night.

The below pictures give an impression of tenement living in the fifties:

Living room – with beds for the children

“Master” bedroom

Kitchen

Buy Irish

The Irish government is advising against any non-essential travel to prevent the spread of Covid-19. Therefore, you should not visit Ireland for the time being. This also means that many small Irish businesses that are dependent on tourism are struggling. Why not make Ireland come to you and at the same time help some of these entrepreneurs?

Genealogy.ie is supporting the “Champion Green Campaign”. This is aiming to get people and businesses to pledge to commit to supporting local to help our communities recover. You can find more information by clicking on their logo below, the green butterfly.

With that in mind, below you will find short descriptions of and links to a number of Irish marketplace websites where you can order Irish made gifts, jewellery, crafts, foods, and lots more for delivery to your home.

-

A directory of 384 independent Irish producers who deliver to your door. Help support your local community and economy.

A directory of 384 independent Irish producers who deliver to your door. Help support your local community and economy. -

Website directory providing free listings of SMEs in Ireland who sell online.

Website directory providing free listings of SMEs in Ireland who sell online. -

The Doorstep Market is a one-stop shop for small, independent Irish businesses, and consumers who want to support them.

The Doorstep Market is a one-stop shop for small, independent Irish businesses, and consumers who want to support them. -

Individually crafted gifts, made to inspire and charm. Handmade with love by over 100 passionate and creative Irish makers and designers.

Individually crafted gifts, made to inspire and charm. Handmade with love by over 100 passionate and creative Irish makers and designers. -

Cuando.ie is a Premium Irish Online Gift Marketplace that brings together in one place fabulous gifts by Makers & Designers all over Ireland.

Cuando.ie is a Premium Irish Online Gift Marketplace that brings together in one place fabulous gifts by Makers & Designers all over Ireland. -

We draw ideas from around us - from the landscape, the weather, the people. This is how our craft comes to life. This is Design Ireland. Find your own inspiration here.

We draw ideas from around us - from the landscape, the weather, the people. This is how our craft comes to life. This is Design Ireland. Find your own inspiration here. -

Kindle e-book written by Michael van Turnhout. A fictional novella offering crime, Irish history, romance, and Irish folklore.

Kindle e-book written by Michael van Turnhout. A fictional novella offering crime, Irish history, romance, and Irish folklore.

Note: we hold no interest in these stores, nor have we received any payment – money or otherwise – to display them here. The listings also do not constitute a recommendation of any kind and we are not responsible for any of the services and/or products. The only exception is “The Curse of the Cliffs”, which is an e-book written by Michael van Turnhout.

The Curse of the Cliffs

MICHAEL VAN TURNHOUT is the husband of the founder and MD of Genealogy.ie, Jillian van Turnhout. He has written a number of articles about Genealogy and Local History, which were published in both Irish and North American magazines. You can download these on our website. Recently he also tried his hand at a fictional novella, but with a base in real Irish history and set in a real Irish village.

This fictional novella offers crime, Irish history, romance, and Irish folklore. Set in Ireland in 1935, it tells the story of a young woman, Sally, who falls in love and gets married. The newlyweds are ready to start their new lives on a farm called “The Cliffs”, as it is situated on a cliff edge on the Irish river Funshion.

The farm and river are surrounded by history: there are the remains of a castle, a ruined church, an obelisk and it is near an old mill-town. All feature in the book as a background to its story. And all – from farm to town – exist in reality.

But not all is good. Warned of a curse, stories of the past come to haunt Sally. She learns about the gruesome history of the farm, throughout Irish history. But even in the present, all is not what it seems. Is the farm cursed? And why? Is Sally in danger? Or is she just imagining things because she recently lost both her parents? Helped by farmhand Stephen Sally discovers the truth.

Available for your Kindle for only £3.86 (just over €4 or just under $5) from Amazon. Click below to go to their store.

Epidemics in Ireland

The oldest possible epidemic in Ireland dates back to the sixth century. We actually don’t know if there was an epidemic – it is believed there was one because many monasteries were founded in the sixth century. The thinking is that a plague epidemic caused a rise in religious fervour. Unlike Covid-19, which is a virus, the plague is caused by bacteria. The bacteria are spread by fleas.

We know there was an epidemic, known as the yellow plague, active in Ireland from 664 to 668 and again from 683 to 684. The second one was especially deadly for children, as a lot of adults had gained immunity during the first outbreak.

It wasn’t just plagues. We have descriptions of outbreaks of fever in Ireland since the 12th century. Fever would be endemic in Ireland, with the disease still around in the 19th century.

In the mid-fourteenth century, it was again the plague which wreaked havoc. This would be the most famous outbreak of the disease. It is thought that the “Black Death” as it was called, killed 30-60% of the European population. During the outbreak, it was believed rats were spreading the disease (bacteria were still unknown). This led to rats being hunted down and killed in great numbers. Causing the fleas that were living on the rats to spread and infect even more people! There were further outbreaks of this terrible pestilence until the early eighteenth century.

Another disease that is spread by lice is typhus. During the Famine, hunger was already having a devastating impact on many of the poor. They often had to leave their homestead, expelled by landlords for not paying rent or leaving to find food. In the hospitals, workhouses and on the ships to North America they huddled together for warmth and lack of space. This formed ideal circumstances for the spread of lice and with them the disease. It started in 1846 in the West of Ireland. It reached Ulster in the winter of that year. It is thought 20% of people in Belfast were infected. Although widespread among the poor, still more prevalent was the aforementioned fever, which also became epidemic during the famine. Interestingly it was among the higher social classes that typhus – more deadly than fever, mortality if untreated can be as high as 60% – was more widespread. It is thought it was contracted by those exposed to the disease (clergymen, doctors, member of relief committees) and then spread to their families, etc.

The famine was accompanied by several other diseases such as dysentery and smallpox. Like fever, these had also long been endemic in Ireland but swept the country epidemically during these years. And then in 1848-1849 Asiatic cholera became pandemic.

Dysentery is spread by flies, by direct contact, or by pollution of the water by faeces infected with the bacteria. Like typhus, it became widespread in Ireland during the terrible winter of 1846-47. It was especially the area of West Cork that was badly affected.

Smallpox is no longer active thankfully. Like COVID it is a viral disease transmitted by airborne droplets. Attacks would last for approximately 6 weeks and would work its way through a family. So, it would often afflict families for months. This would often mean even more poverty for already impoverished people, as they lost their earning power for a prolonged period.

Even in the 20th century, Ireland has had epidemics. Tuberculosis was one. Its common name was consumption as the patient was “consumed” by weight loss and breathlessness. According to research by the Irish Red Cross Journal, 12,000 young Irish adults died of TB in 1904. Mortality remained high in the 1920s and 1930s, especially among children. Despite years of non-stop efforts, it was not until the 1950s that TB started to decline and only by the 1970s it had all but vanished from our shores.

Another one was polio. This is again a viral disease, spread through person-to-person or faecal-oral contact. Its mortality is between 5 and 10%, but in some outbreaks mortality of over 25% has been reported. Unlike COVID, it especially affects children under 5. There is no cure but can be prevented with vaccines. In Ireland, vaccines were introduced in 1957, after several bad outbreaks. Ireland had its first registered epidemic of this disease in 1942. There were further waves in 1947, 1950 and 1953 and in 1956 in Cork. Advice from authorities might sound familiar: closure of swimming pools and schools, advice on handwashing and on general hygiene, warnings against unnecessary travel into or out of communities where the disease was prevalent. And for the vulnerable, in this case, children, to avoid crowded places and gatherings of other children. Circus, swimming and tennis tournaments and GAA activities were either postponed or abandoned. Social and commercial life was badly affected. The epidemic was over around May 1957. It was not completely gone but had returned to “normal” levels.

Like the rest of the world, Ireland is now suffering from the outbreak of the COVID 19 pandemic. The whole country now sees restrictions even more severe than those in Cork in 1956. History shows the importance of adhering to these restrictions: many epidemics/pandemics have seen several waves and high levels of mortality, esp. among the vulnerable. By social distancing, working from home, not having large gatherings, festivals, etc. we should be able to minimise the impact. And nowadays many can work from home and we can stay into contact via social media. So there are no excuses. And the good news: many vaccines have been developed and most of the diseases mentioned have been eradicated or their prevalence has been drastically reduced.

Stay safe, stay healthy, stay firm!

Sources:

- Pádraic Moran, NUI Galway

- Infection In A Village Community In The 19th Century And The Development Of The Dispensary System, Presidential Address to the Ulster Medical Society, Thursday 11 October 2007 by Dr John B White, General Practitioner

- Epidemic Diseases of the Great Famine, published in 18th–19th – Century History, Features, Issue 1 (Spring 1996), The Famine, Volume 4 and The 1956 polio epidemic in Cork, published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 3 (May/Jun 2006), Volume 14 by Laurence Geary, who is a Wellcome Research Fellow in the History of Medicine at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland

- https://www.irishexaminer.com/ireland/health/the-silent-terror-that-consumed-so-many-128709.html

Elections

This week we had both local and European elections in Ireland. Fine Gael, Fianna Fail and Labour (the traditional parties) held their own. Sinn Fein did badly and the Green Party did exceptionally well.

So who are these parties, with their strange names? Irish parties defy the traditional stereotyping of “right”, “left”, “liberal”, “Catholic”, etc. Here is a very short and high level overview.

The oldest party in Ireland is the Labour Party. It is a social-democratic political party. (Communism never really caught on in Ireland). Founded in 1912 in Clonmel, County Tipperary, by James Larkin, James Connolly, and William X. O’Brien as the political wing of the Irish Trades Union Congress. In those days – and ever after – it was overshadowed by the national parties, which strived for political autonomy or independence. Labour has been traditionally the third largest party in Ireland, although this position has been challenged in the last years.

Sinn Fein is not a party – it is multiple parties! The orginal Sinn Fein was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith. It was subsequently heavily infiltrated by the Irish Republic Brotherhood and became a vehicle for its struggle for independence. In the 1918 election (then still part of the UK general election) it caused a major upset by beating the up to then dominating Irish Parliamentary Party led by John Dillon. The latter had supported the UK World War I effort by calling for Irish men to volunteer for service. The results were devastating as the picture shows:

After the War of Independence Sinn Fein broke in two: the followers of Eamon de Valera, who had opposed the Treaty with the UK, eventually formed Fianna Fail. After a short period in opposition, it won the election after the 1929 financial crash. Although it did spend some short periods in opposition, the party would be the party of government until 2011. In that year, another financial crash ended this period of dominance and it is now neck and neck with Fine Gael.

This party was also an offshoot of Sinn Fein. Its main component, Cumann na nGaedheal, was formed after the Civil War by the followers of Michael Collins, representing the pro-Treaty side. After its defeat in 1932 it merged with two other parties, to better compete with the Fianna Fail juggernaut. These parties were the National Centre Party (representing mostly farmers) and the National Guard (popularly known as the “Blueshirts”, whose leader turned out to be a fascist and was therefore quickly deposed).

The party currently known as Sinn Fein has its roots in Northern Ireland. Here, discrimination against Catholics boiled over from the 1960’s, leading to a bloody war of terror. This was not ended until 1998, when the Good Friday Agreement was signed. This Sinn Fein has always had a presence in the Republic of Ireland as well, but it was only after it forsook violence, it became a large force in politics. Despite its heavy losses in this election, it is still the third most popular party in Ireland.